The (real) History of Anaesthesia

|

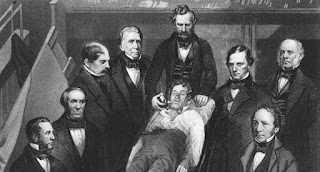

| Dr William Morton pretending to invent anaesthetics |

Anaesthesia: a state in which someone does not feel pain, usually because of drugs they have been given (Cambridge English Dictionary)

If you do a Google search for “history of anaesthesia”, most search results suggest that anaesthetics were invented by Dr William Morton of Boston in 1846, who was the first to use ether to perform a dental extraction. There are occasional nods in the direction of earlier, plant based anaesthetics, mainly to dismiss them as unimportant. I particularly like the comment by the Royal College of Anaesthetists of the United Kingdom, who say:

“Although a number of drugs used in modern anaesthesia have their origins in substances found in plants, those early concoctions are irrelevant to the development of effective, drug-induced anaesthesia.”

And of course, I completely agree. If I am going to have a painful surgical procedure performed, I would much rather have a modern anaesthetic than a plant based “concoction”.

That is, provided everything remains the same as today. The 10,000 mile long supply chains of raw materials and finished pharmaceutical products remain intact, with no interruptions due to fuel shortages or hostile action. The global economy remains the same, with international electronic banking providing the means for manufacturers to pay the suppliers of raw materials, and users to pay manufacturers, and there’s no shortage of money. The climate remains the same, so that (for example) opium poppies currently grown commercially in Australia continue to flourish in Australia. The solvents used in manufacturing processes, for example, alcohol, chloroform, benzene and ammonia, remain available in industrial quantities at a reasonable price. And so on.

But what if they don’t? Wouldn’t it be a good idea to have a Plan B? So with this in mind, I would like to present the real History of Anaesthesia, which is older and stranger than you might think.

The use of anaesthetics for pain relief is as old as civilisation itself. Alcohol and opium are said to have been used by the Sumerians as long ago as 3400 BC. As the Sumerian civilization declined, this knowledge of anaesthetics passed to the Babylonians and then to the Assyrians, Egyptians, Indians and Chinese.

Fast-forward to the Greek and Roman Empires (330 BC – 476 AD). I am particularly interested in the Romans’ use of anaesthetics because their empire lasted for hundreds of years and covered most of the Mediterranean world from North Africa to Scotland. They were an aggressive, expansionist, military empire which absorbed useful knowledge from the territories they conquered: for example, wealthy Romans would employ a Greek tutor, or pedagogue, for their children because of the status of a Greek education. They maintained large armies, fought countless wars and had many injured soldiers. Physicians and surgeons travelled with their armies, and if anyone knew about anaesthetics, it would have been the Romans.

|

| For God's sake man, get your patient to lie down |

Contemporary Graeco-Roman texts tell us that by Roman times, several plant based anaesthetics were in use. The anaesthetic of choice for the Romans was a combination of opium from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) and European mandrake root (Mandragora officinarum) which have complementary properties: the opium provided pain relief, the mandrake induced semi-consciousness. Other plant based anaesthetics included:

|

| A large white bryony root from my allotment |

Bryonia dioica (English mandrake, white bryony). Has a similar combination of toxic alkaloids to European mandrake, and is generally interchangeable with it, but grows better in a cool Northern climate.

Hyoscyamus niger (henbane): induces drowsiness or unconsciousness depending on the dose.

Conium maculatum (hemlock). Best known as the plant used to execute Socrates, the ancient Greek philosopher. In large doses it paralyses the respiratory muscles causing death, but in smaller doses it induces muscle relaxation and makes surgery easier.

Aconitum lycoctonum (monkshood, wolfsbane). Causes paralysis, like hemlock. Has also been used as an arrow poison.

Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade). A nerve agent like hemlock and monkshood. Used in small doses by the ancient Greeks to induce drowsiness and numbness before surgery. Used in larger doses by the Romans as a biological weapon (poisoning the enemy’s water supplies). The Emperors Claudius and Augustus are also reputed to have been poisoned with it.

Datura stramonium (thornapple, jimsonweed). Causes altered mental state including pronounced amnesia: useful if you want to forget about the trauma of having a limb amputated.

All of the above preparations can be useful in therapeutic doses but fatal in overdose.

Now let’s fast forward again to the time of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). According to most accounts, there was no policy of administering anaesthetics or painkillers during surgical procedures, even very painful procedures like amputations. It is unclear whether this was because anaesthetics were unavailable, or because it was not military policy, or because the surgeons didn’t know they existed. The best you were likely to get was a swig of alcohol, a leather strap to bite on and four strong men to hold you down. But how can this be, when the Romans and Greeks knew of and used a large number of plant based anaesthetics? In effect, by Napoleonic times, the science of anaesthetics appears to have regressed 5,000 years, back to the standards of the ancient Sumerians.

|

| Amputation, 19th century style |

The answer is probably to be found in the religious beliefs prevalent in the Dark and Middle Ages following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. After the last Romans left Britain in 410 AD, there were many people left behind who were familiar with Roman culture and Roman medicine, and this knowledge would have been passed on from one healer to another and from one generation to another, often in monasteries where monks kept “physic gardens” and would copy and recopy Roman manuscripts in order to preserve them.

Throughout Europe, the Christian Church had an increasing influence on everyday life, reaching a peak of religious fervour around the 14th to 17th centuries. At that time, you could be imprisoned or executed for a great many religious transgressions: being Protestant in a Catholic country, being Catholic in a Protestant country, being Jewish or Muslim anywhere, not going to church often enough, or challenging orthodox Church teachings (Galileo was imprisoned in 1633 for the heretical belief that the earth revolved around the sun). Religious significance was attributed to even the smallest things in life; for example, if the shapes of leaves, flowers or fruits resembled a part of the human body, that was thought to be a sign from God that they would heal that part of the body (the Doctrine of Signatures).

The germ theory of disease would not be understood for another 200 years. If a crop failed, an animal sickened, a baby died or a plague like the Black Death swept across the land, people would look around for someone or something to blame. Clearly they had been poisoned – and the most obvious suspect for the poisoning would be the person who grew poisonous plants and knew how to use them – in other words, the village healer or midwife, who was obviously a witch and in league with the Devil. So herbal medicine practitioners across Europe were executed, imprisoned and had their property confiscated, and those who avoided the attention of the church probably decided that it wasn’t a good business model and quietly gave up. After a few hundred years of persecution, the practice of using toxic plants for medicinal and anaesthetic purposes had virtually died out, and anaesthesia wasn’t rediscovered until the mid-19th century when people thought (incorrectly) that they were inventing something completely new.

Which brings us back to our starting point. Nitrous oxide (laughing gas) was used in 1844 to induce anaesthesia while performing a dental extraction, ether was used in the same way in 1846, chloroform was used in 1847, and the first rapidly acting intravenous anaesthetic (thiopental) was used in 1934, followed by a host of other anaesthetic agents.

I would like to finish this post with a warning: don’t be complacent. At the beginning of this post I invited you to consider what our Plan B should be if our usual anaesthetics became unavailable. Remember that all civilisations and empires come to an end, either gradually or suddenly. I have already mentioned a few of them - the Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Greeks and Romans - and I could mention many more – the Medes, Persians, Sassanids, Mayans, Aztecs, Incas, Spanish, Ottomans and the USSR. All of them have two things in common: they all declined or collapsed, and until it happened, they all thought it could never happen to them. Decline and collapse are part of the normal life cycle of a civilisation, and there is no reason to suppose that we will be any different. Good luck.

Slaynt vie, bea veayn, beeal fliugh as baase ayns Mannin

2.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment